«Theatre should be a human right»

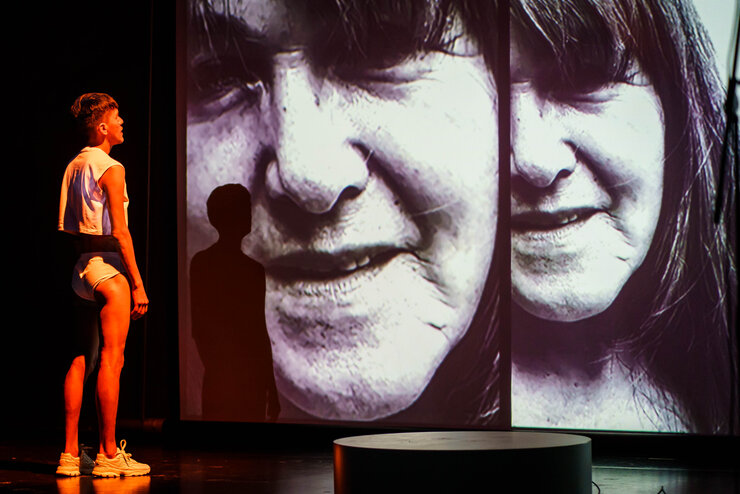

After wowing audiences with «Soliloquy» at the Zürcher Theater Spektakel in 2022, Tiziano Cruz is now returning to Switzerland with his latest piece «Wayqeycuna». The works of the interdisciplinary artist, who lives in Buenos Aires, combine visual and theatrical language, performance and artistic intervention in public space. Tiziano has been a grantee of the Fondo Nacional de las Artes and the Instituto Nacional del Teatro ARG. He was a winner of the Bienal de Arte Joven 2019 and winner of the ANTI award, Finland, 2023. He is the founder of the Cultural Management Platform ULMUS, dedicated to the mediation between different cultural organizations in Argentina and neighbouring countries. He has worked as a Content Producer at the Centro Cultural Recoleta in Buenos Aires. His works have toured Chile, Brazil, Mexico, Canada, Portugal, Spain, Switzerland, Germany, Finland and the USA. Our curator Lea Loeb conducted an interview with Tiziano Cruz to talk about «Wayqeycuna».

Tiziano, thank you very much for agreeing to do this interview. We are delighted that you will be presenting your new play «Wayqeycuna» in Zurich this August. Your last play «Soliloquio» was shown two years ago at the Theater Spektakel, it was the first presentation of your work in Europe.

Yes, «Soliloquio» was the work with which I internationalised my artistic work. Now I'm coming back to Zurich with my latest work. «Wayqeycuna» is part of a trilogy of autobiographical works that I began developing in 2015.

How does this piece relate to the other two parts of the trilogy «Tres Maneras de Cantarle a una Montaña (Three Ways to Sing to a Mountain)»?

The first piece was dedicated to my father. It was called «Adiós Matepac» and was an essay about the memory of farewell. The second piece, «Soliloquy», is dedicated to my mother. Finally, «Wayqeycuna» is dedicated to my siblings. Each of these three pieces follows a song in its structure. The three works are linked by a common thread, the death of my sister in 2015. She died at the age of 18 in a hospital in the north of Argentina due to complications from childbirth. She was denied medical help because of her origins. This death was not only a tragic event for my family, it is also a collective event. Because in Argentina, not all bodies are equally valued. In my work, I talk about the structural racism, neo-colonisation and xenophobia that prevail in my country. My sister's case is not an isolated one, but something that is recurring in hundreds of communities in the region that I come from. All three pieces of my trilogy deal with this life-threatening, structural inequality from different perspectives. In addition, community customs and indigenous philosophies run through all parts of the trilogy.

What is the meaning of the title «Wayqeycuna»?

«Wayqeycuna» is a word from the Quechua language. It means «my brothers and sisters» and stands in contrast to the other two pieces, whose titles are based on Western culture. «Matepac» is the Greek equivalent of the word «father». «Soliloquy» means «monologue». The term comes from Aristotelian theatre theory and refers to someone who speaks to himself or herself and at the same time shares a reflection with the world. It was clear to me that the last part of the trilogy had to have a title from my own language. I see my theatre work as a critique of Western art and the Aristotelian theatre structure. It allows me to detach myself and return to the source. In a way, «Wayqeycuna» is a return to my roots. I have chosen my mother tongue to name that which, if it is not named, does not exist. In indigenous languages, a word doesn't just mean a word, it can also be a phrase. «Wayqeycuna» does not simply mean «brothers and sisters», but «MY brothers and sisters», which is much more inclusive and refers not only to my blood brothers and sisters, but also to my brothers and sisters in the communities. My relationship with them takes centre stage.

This third part of the trilogy is about death and in particular the mourning rituals that are celebrated in your region of origin. Can you tell me more about this?

«Wayqeycuna» marks the end of almost eight years of research that began with the death of my sister. In the course of this work, I have come to understand that grief does not stop, that it will never end. Unlike Western cultures, I don't understand life as a linear process where you are born, live your life and then die. Indigenous cultures have a different idea of life and death, namely as a cycle in which we come and go in certain ways and are present in different ways. In fact, this understanding allows for a different, gentler grieving process. I would also like to share that with the audience through this piece.

Can you explain this in more detail?

In Western cultures, death means the end. And the bereaved often cannot get over their grief, pain and sorrow. In our indigenous cultures, things are different. The end of life on earth also means joy. We believe that when a person leaves this earthly plane, they enter the so-called «pacarina». The pacarina is a place where souls rest, from where they come to the earthly plane and leave again. Just a few weeks ago, on May 3rd, the Day of the Chacana was celebrated. In our indigenous calendar, Chacana is a cosmic bridge that connects the two worlds every year. All the people who have died – my mother and my sister – become ancestors who help guide us on our path so that we are able to move through life in a collective and communal way. I think this is one of the great wisdoms of our culture. Because now the deceased accompany us for a lifetime, until we also become ancestors and become companions for other people who will come after us. This gives us peace of mind when dealing with the disappearance of beloved bodies. And I'm talking especially about the violent disappearance of bodies here in Argentina, which we indigenous cultures are constantly confronted with. My mother, who died this March, the day after the premiere of «Wayqeycuna» after a short, serious illness, is also a victim of the Argentinian healthcare system. Because to this day, two months after her death, the cancer medication she so desperately needed has still not arrived. It is a fact that some bodies in Argentina are worth much more than others.

This play is about all that. On the one hand, it is a poetic and very personal evening, on the other hand, it is a documentary piece. I show what it is like to live in the area I come from, a village in the mountains, cut off from all the big capitals and the big technological advances. In the work, I show a video of a visit to my community. It is a community full of paradoxes, in which the triumph of colonialism is inscribed as much as the eternal resistance.

In «Wayqeycuna» there is a video showing a procession in which the inhabitants of your village carry a statue of the virgin up the mountain. What role does Christianity play in your community?

The film shows a procession or a «misachico», as we call it in our culture. In fact, a statue of the virgin is carried up the mountain on the shoulders of the village community. Before this practice became widespread, our indigenous cultures had related practices. There were processions there too, but it was not the statue of the Catholic virgin that was carried, but the mummified bodies of the deceased of our people who had passed on to the pacarina. At the end of October and the beginning of November, during the week of the dead celebrated throughout Latin America, the secular remains were dug up. Each community had its own ancestors, who were carried on the shoulders or backs of neighbouring communities. This was a great celebration in honour of the deceased, who were called back from the pacarina to guide the community through the coming year. With the arrival of the Spaniards, especially the Jesuits, who violently conquered our territory, a law was passed that forbade the exhumation of the «Indians» – as they called us at the time – and obliged us to replace the bodies with Catholic saints or virgins. This custom has since found its way into the indigenous communities.

So the ritual is a mixture of an indigenous ritual and a custom introduced by the colonisers and missionaries?

My community, just like other indigenous communities, have found ways to continue to celebrate and stay in touch with the reincarnation of our ancestors. We have had to compromise on certain issues in order not to lose all of our traditions: Since we could no longer dig up our brothers and sisters and ancestors, we replaced them with bread figures. These are the same bread figures that appear in the play «Wayqeycuna». These bread figures play an important role in our community. They embody the person who has left us or represent the environment, flora or fauna, in which that person is to be reborn. The bread figures are baked by the community as offerings during the week of the dead, in memory of the deceased loved ones. Throughout history, our indigenous communities have found many ways of resisting in order to preserve our own traditions.

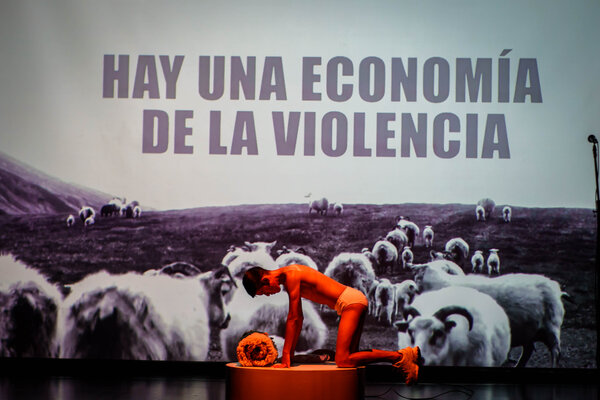

For me, the play «Wayqeycuna» has two levels: On the one hand, it invites the audience to get to know our indigenous cultures a little better and to become part of a community for the duration of the play. It proposes a world in which we all work together, in which we can all see ourselves as part of a common whole. On the other hand, the play is very political. It problematises and denounces inequalities and makes us all responsible for working together to eliminate them.

Most Argentinian artists who are internationally renowned and travel to the big European festivals in Europe, for example, are white. What is it like for you to travel around the world with your pieces and embody a «different» Argentina?

Well, first of all, I undeniably feel a great responsibility. I am probably the first indigenous artist – at least in Argentina – to travel so much and have this international visibility. I believe that it is my duty to open more doors so that the economic and symbolic benefits are not just for me, Tiziano Cruz. But that as an artist, as the indigenous person that I am, I can really make a contribution to other artists and collectives. That seems to me to be the big challenge, and that's exactly what I'm trying to do with my work «Wayqeycuna». With this piece, I am also trying to empower representatives of other marginalised communities around the world.

When you talk about Argentina, many people automatically think of Buenos Aires. In fact, Argentina is an extremely complex country that is not adequately represented by political, economic and cultural centralisation. Not everything is about Buenos Aires. My presence at these large, international festivals is symbolic of this counter-narrative, of the recognition and complexity of identities, it celebrates decentralisation. In Argentina, as everywhere else, there are peripheral centres where people – artists, academic and non-academic thinkers – live who make important contributions and who also deserve to be heard. Highlighting this is my great task and the driving force behind my work.

Do you notice a change in relation to this discourse in the art world?

Indigenism is an issue that has been on the global agenda for a long time. We have always been talked about. There have always been great directors, artists and thinkers who have talked about what we are like, how we feel, how we live and what our needs are. Now, for the first time, it is possible to express first-hand what our needs are. For us indigenous artists, this is a big step forward. Now it is also our responsibility to open these doors to other communities and other artists.

I can't stress enough that it's not about victimisation. It's about addressing realities, problematising them and proposing common approaches to eliminate the existing inequalities. My personal goal is that we won’t have to talk about violent extractivism of natural resources or child slavery forever. But that we can also talk about other things in our art. For example, about the meaning of the sky, the earth, water, in a more beautiful way. But today it is urgent to denounce or put on the agenda all these things that we indigenous communities are confronted with every day. Not only in Argentina, but all over the world.

What does theatre mean to you?

For me, theatre is a bourgeois practice, a practice of the upper middle class. It is an art that is made for the few. That's why it's a revolutionary act for me to dedicate myself to making theatre. Because I am a person who comes from the periphery, who comes from a poor, indigenous family and who is homosexual. All of those characteristics define me and, at the same time, have long made it unthinkable that I could even exist in the world of theatre. Theatre must open up and truly become a culture for everyone, as I demand in my work. Theatre – like water – should be a human right; all manifestations of art should be able to be just that. I have decided to dedicate myself fully to this task – opening up the theatre – because I truly believe I can make a difference here. I want to give other marginalised people access to theatres so that they can occupy large stages that they have been denied in the past or to which they themselves thought they had no access – either as artists or as audiences. I want to break through these invisible boundaries that society imposes on us. That's where I see my role in theatre.

There is still a long way to go, but I think there are trends pointing in the right direction. And I want to trust that this change will happen.

Credits

Interview: Lea Loeb

Photos: Matías Gutiérrez und Diego Astarita

translated from German into English by Franziska Henner